“The sky is radiant and for a fortnight we have been living in miraculous new conditions: a home that is heavenly, because everything is sky and light, space and simplicity,” Le Corbusier wrote to his mother in 1934. He was rhapsodizing about his new apartment/workspace in Paris, where he would reside for more than three decades with his wife, Yvonne, their dog, Pincea, and their housekeeper. Le Corbusier loved the space so much that he stayed there until his death in 1965.

Occupying the top two floors of Immeuble Molitor — the world’s first apartment building with fully glazed facades and among the architect’s 17 UNESCO-listed buildings — the 2,600-square-foot penthouse was recently reopened to the public after a two-year renovation.

“One option was to return to the initial state when Le Corbusier and Yvonne moved in,” says architect François Chatillon, whose firm, along with a multidisciplinary team, was tasked with the restoration overseen by Fondation Le Corbusier. “But it seemed to us more appropriate to integrate the marks of 30 years of use, where the experience of the place resulted in constant transformations in which the architect did not stop testing new experimental mechanisms, introducing new materials, experiencing the polychromy.”

Born Charles-Édouard Jeanneret in 1887 in La Chaux-de-Fonds, Switzerland, the architect moved to Paris in 1917 and never looked back. In 1931, with his practice well established, he and his associate and cousin, Pierre Jeanneret, were commissioned by a private developer to design an apartment building in Paris’s 16th arrondissement on a plot bordering the commune of Boulogne.

Living at the time with Yvonne in a cramped apartment in the St. Germain-des-Près quarter, he decided to reserve the seventh and eighth floors of the new structure as their dwelling, incorporating a studio for pursuing his first love: art. Comprising a living space, studio, guest room and rooftop garden, the apartment benefited from the building’s then-groundbreaking construction approach. Involving a frame of reinforced concrete, this allowed for an open floor plan and a “free-floating” curtain wall made of Saint-Gobain glass (including the now-famous Nevada blocks), which together resulted in light-filled interiors, sweeping views and fluidity. Here is a tour of the highlights post-renovation.

This central space connects the four main parts of the apartment. Here, Le Corbusier’s free plan and “architectural promenade” concept are visible. The dominant spiraling staircase — with a single pole in place of a handrail — leads to the eighth-floor guest room and the rooftop garden. Two large pivoting doors welcome you to either Le Corbusier’s studio or the apartment. When the doors are open, you experience the visual continuity of the space (emphasized by the continuous stoneware-tile flooring) and the light streaming through the glass curtain walls, skylights and other windows. Opposite the staircase is a bright blue wall. Le Corbusier used different wall colors to distinguish different areas.

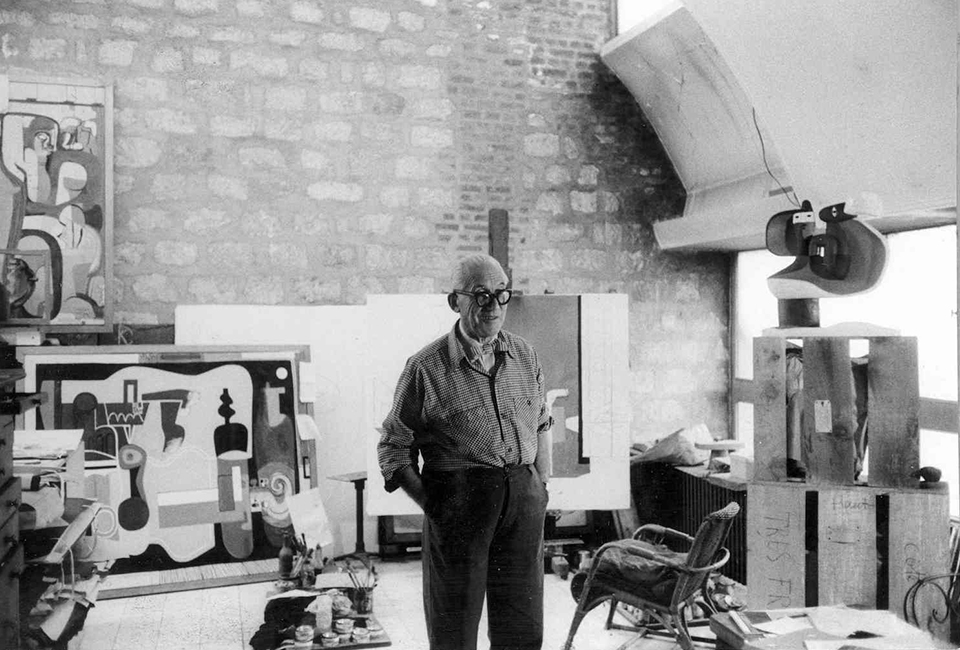

Before heading to his office in the afternoon, Le Corbusier would spend the morning painting in this light-filled space dominated by a 40-foot-long barrel vault and a stone wall with exposed brick.

“Stone can speak to us; it speaks to us by means of the wall,” he said. “Close to us, in contact with our hands, it is a skin, rugged and yet well-defined. This wall is my daily friend.” The whitewashed wall presented a traditional counterpoint to the modern glass walls on the east and west sides of the studio. So much light came in that Le Corbusier was constantly trying out means to diffuse it, including the wood panels you can see today on the Paris-side facade. Along with the largest area, for painting, the studio also included a corner study where he wrote.

The second pivot door in the entrance hall leads to the salon, which feeds into the dining room. Here, a vermillion wall is part of the encasement built around the service elevator, its machinery and the chimney. (Throughout the apartment, colors were restored as closely as possible to those at the time of Le Corbusier’s death.)

To reveal the history of Le Corbusier’s transformations and the restoration process, the layers were left visible, creating something like the architect’s color keyboards. The room’s furnishings include the LC3, or Grand Confort, armchair codesigned by Le Corbusier, Charlotte Perriand and Pierre Jeanneret; the LC3 sofa; and the LC1 slingback chair. Design firm Cassina supported the restoration of the furniture, “which was performed by skilled craftsmen directly in Paris,” says Barbara Lehman, head of the Cassina Historical Archives.

In addition, the company produced the missing “cowhide” carpet, “made with ‘squared elements’ of leather stitched together,” Lehman says. Also present are what the architect referred to as his “poetic reaction objects.” “These are shells, stones, bones, pine cones or pieces of wood picked up by Le Corbusier,” says Isabelle Godineau, head of archives and exhibitions at Fondation Le Corbusier.

Beneath another arched ceiling, the dining room benefits from a glazed facade. It opens onto a balcony that runs the length of the connected kitchen, dining room and bedroom and offers views of the Boulogne commune. In 1949, a stained-glass window made in Reims by artist Brigitte Simon was incorporated into the glass facade just in front of the dining room table, designed by Le Corbusier. Surrounded by four Thonet chairs and featuring a marble top and two trumpet-like legs, it was inspired by a mortuary table he saw in a dissection room.

Adjacent to the dining room and also accessible via a service door from the passageway that leads to the servant’s room, the kitchen is distinguished by its built-in furniture, created by Perriand, who worked in Le Corbusier’s studio. An upper cabinet and lower storage unit, both with sliding doors, are joined together by slender tubes similar to those of the entrance staircase. The double sink and counter tops are pewter. White vertical subway tiles adorn the walls, while windows at the sink, including Saint-Gobain Nevada blocks, bring in light.

From the dining room, you pass into the bedroom through a massive door with a wardrobe attached to its other side. It’s an appropriate entry, or exit, for a rather funky space inspired by Le Corbusier’s love of ocean liners. With a headboard attached to the bright blue wall behind it, the bed is raised high on thin poles to provide husband and wife with a view of the Boulogne commune.

Next to Le Corbusier’s shower, a yellow door conceals a full-length mirror. Yvonne’s bathroom, with its uniquely shaped door frame and sitz bath, is done in marine blue with mosaic tiles. Historic photos show the painting Still Life, First State by Fernand Léger on the wall next to the bidet. Currently — for security reasons, according to Godineau — the apartment contains no artworks, but it is hoped they can be added soon.

When Le Corbusier secured the top two floors, he also developed the roof at his own expense. Up there, in the curvature between the vaulted ceilings, he redefined it as a “suspended garden,” as he had in earlier projects, like Villa La Roche and Villa Savoye.