Based on the principle “Anything can be a shoe”, this exhibition shows the unbridled imagination and diversity of shoes in fashion. As a transformative, playful and surreal part of one’s clothing, shoes are an object of desire, but also of memory, emotional value and inspiration.

Geert Bruloot and Eddy Michiels, shoe collectors and curators of this exhibition, have spent thirty years collecting fashio-nable shoes that inspire them. Besides hats, garments and archive materials, MoMu houses 200 pairs of shoes of the Bruloot-Michiels collection, to be displayed as privileged witnesses of history, but also to inspire the fashion designers of the future. The shoes in this exhibition are a selection from the Bruloot-Michiels collection, complemented with over 500 masterpieces from the designer archives, shoe and fashion museums, and private and ethnographic collections. They radiate the emotions and amazement that fashionable shoes can cause: that enticing and irresistible siren song that seduces and dazzles.

Geert Bruloot: “Just as Sergei Diaghilev, impresario of the Ballets Russes, told Cocteau in 1917: “Amaze me!”, we invite the visitor to come on a journey with us and be amazed.”

The 1960s futurism of the space age, with Pierre Cardin, André Courrèges and Rudi Gernreich as most famous fashion designers, was expressed in A-line dresses and white vinyl Courrèges boots. New artificial materials such as vinyl, plexi, metal and nylon were used to create the – usually flat and tight-fitting – space age shoes (one could think of Stanley Kubrick’s “2001: A Space Odyssey”, 1968). Thierry Mugler’s 1980 sci-fi futurism shows the power look of the 1980s, translated by gold-lamé and extra high heels into a dominant look that forms a strong counterpoint to the more naïve space look of the 1960s.

Today’s futurism is still aiming for the stars: the graduation shoes created by fashion student Niklaus Hodel, winner of the 2011 Coccodrillo Award and co-founder of the young shoe label WeberHodelFeder, were made from pure aluminium in collaboration with the hi-tech research lab of the Swiss company Sulzer, which also works for the aerospace industry.

Geert Bruloot: “The morning of July 21st 1969, my entire family was in front of the black and white television in great suspense to witness Neil Armstrong’s jump from the bottom step of the Moonlander and so create the most iconic footprint of modern times! As a 16 year old boy, I lived the moment as science fiction becoming reality and the future turning limitless! This “… giant leap for mankind” would forever stay burned in my memory is a sign that everything is possible, as long as you believe!”

Since the cultural revolution of the 1960s, fashion statements and patterns have often employed the colourful, simple and happy symbols from pop culture (smileys, flags, advertising, logos), pop art and pop music. The prêt-à-porter (ready-to-wear) gained dominance over haute couture due to the advantages of mass production and the industrialised consumption culture in America. Shoes can be a striking and colourful starting point for a silhouette in glossy materials such as vinyl and plastics. Beth Levine (USA), Jan Jansen (NL ) and Tokio Kumagaï (JAP) love to use such symbols, and their creations are playgrounds of pop culture references. Even today, young designers keep alluding to Keith Haring, Roy Lichtenstein’s pop art and Andy Warhol’s banana.

Benoît Méléard is one of the most innovative and radical shoe designers you might never have heard of, the star behind trailblazing designs for Alexander McQueen and Hussein Chalayan. Under his own name he created the most uncompromising shoes that challenge the idea and concept of a shoe itself. His graphic, absurd and strongly geometric shoes do not keep the shoes from being wearable and comfortable.

Méléard makes every shoe by hand and works and reworks the shoes until they fit right. His famous ‘O’ collection was inspired by the late Leigh Bowery, and eccentric superstars like Amanda Lepore and Daphne Guinness are large fans of his. His shoes are much appreciated by the lovers of design and some pairs belong to the collections of Musée Galliera and the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris.

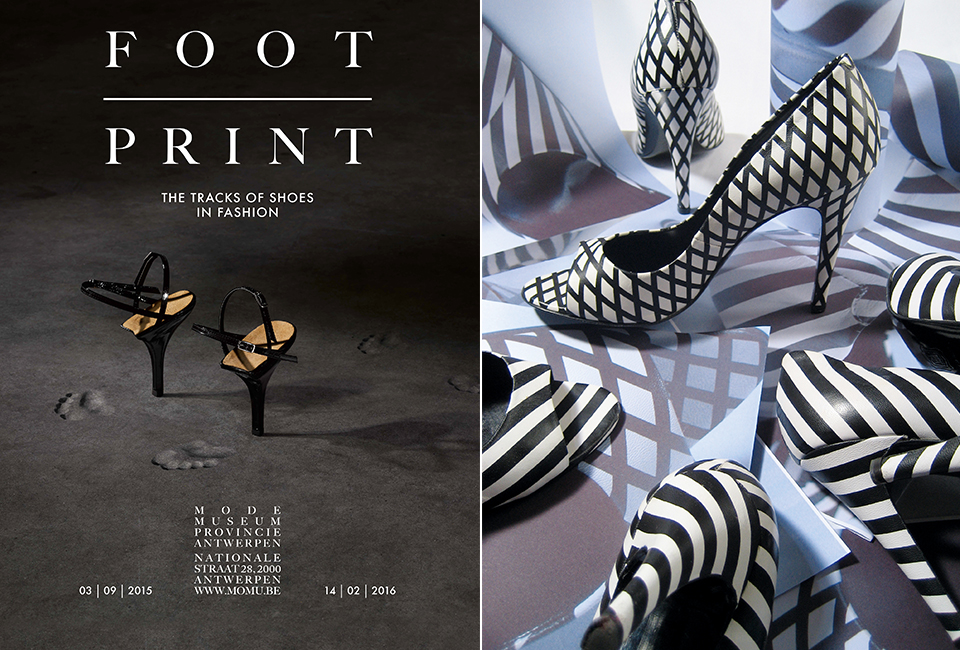

Frenchman Pierre Hardy studied fine art and dance: he went into shoe design as a continuation of his love for movement and drawing, saying “Dancing is like drawing a figure in space with the body.” His graphic talent resulted in a very styled, precise and balanced approach to shoe design, based on constructivism and architecture. Hardy: “We carry clothes, but shoes to carry us: shoes support you and can define the way you walk, the way you dance.” For Hardy, abstraction and sensuality are both integral parts of his design DNA.

Shoes use architectural and sculptural principles more than any other fashion item: from the heel to the toe and the instep, the shoe’s construction and structure determine the view and the way that the foot can relate to the body. It should therefore not be surprising that the fashion designers with the strongest architectural and threedimensional skill focus specifically on shoes: shoes combine the engineer’s technical ingenuity with the sculptor’s artistic flair, as is testified by sculptor Barbara Hepworth who inspired Patrick Cox, or when architect Ettore Sottsass is praised by Pierre Hardy. Oskar Schlemmer (Bauhaus school) saw the movement of puppets and marionettes as aesthetically superior to that of humans, as it emphasised that the medium of every art is artificial. Schlemmer saw the modern world driven by two currents, themechanical and the primitive impulses. He claimed that the choreographed geometry of dance offered a synthesis.