The thing about these guys is that they are so modern. And by modern, I mean contemporary. And by contemporary, I mean recognisable as belonging to the ‘now’. Take for instance, the very first piece presented in this exhibition ‘The Rock Drill’ by Jacob Epstein. If one wanted to reference it to a contemporary image, one would have to say this is definitely the Terminator. Yet, it was created in 1913. That’s 71 years before the movie, by the way.

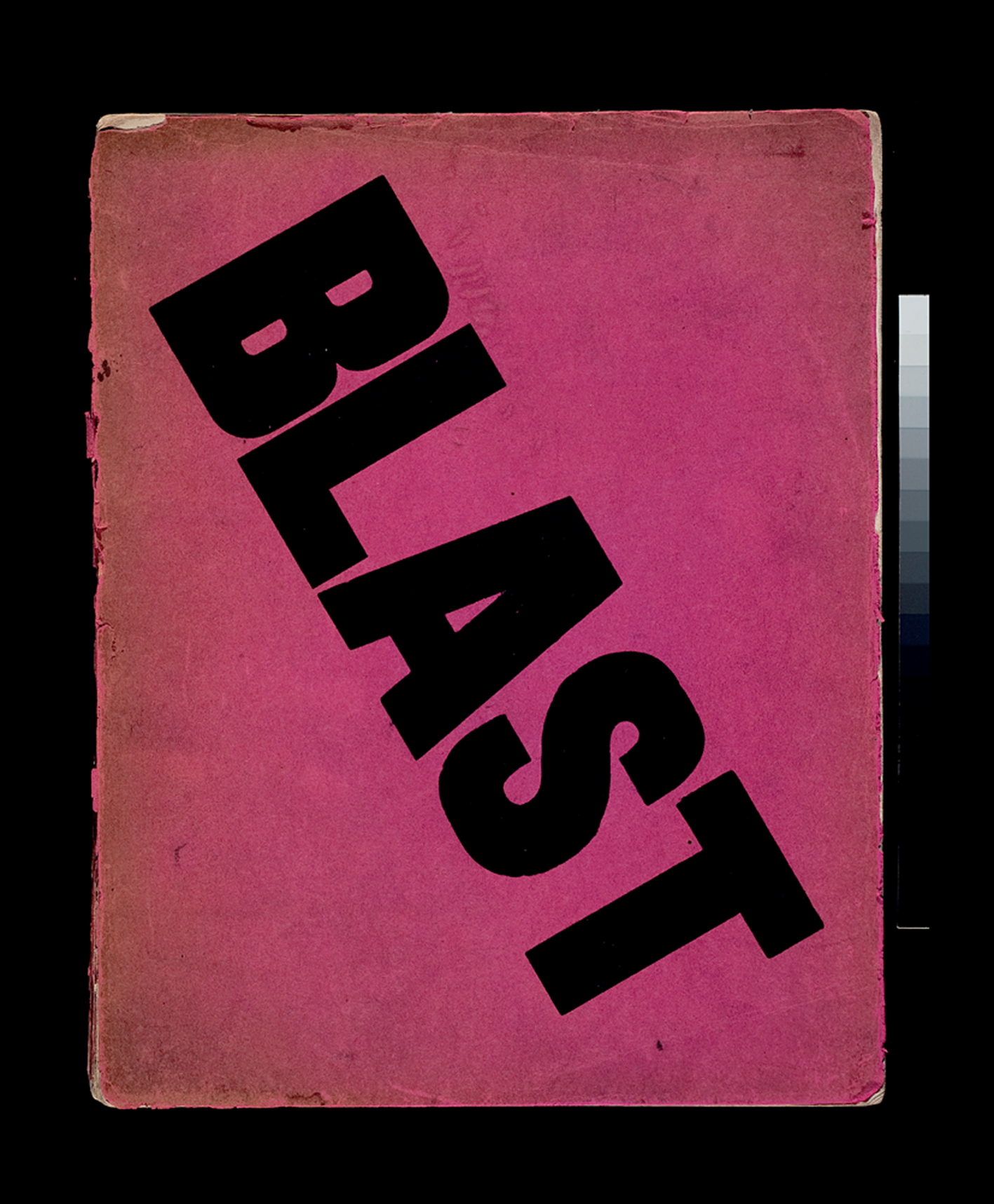

To put things into perspective, it is June 1914, and a group of artists and poets based in London produce a manifesto, published in the form of a review (or magazine), in which they declare their rejection of the Future and of the Past. It’s called BLAST (No. 1), and it ‘blasts’ and ‘blesses’ aspects of European and American culture. Shamelessly anti-Impressionist (and anything French that looked to the past, for that matter), but also very much anti-Futurist, they set out to make their mark as those who would ‘leave Nature and Man alone’*, yet drawing on ‘England’s mechanical inventiveness’ would provide a ‘venue for vivid and violent ideas that could reach the Public in no other way’. Their leader is the artist and author Wyndham Lewis. They call themselves Vorticists and declare: LONG LIVE THE VORTEX!

The movement’s protagonists (or ‘Primitive Mercenaries’, as they like to call themselves) are constantly fighting. Members come and members go. There is a constant struggle with Roger Fry (representing establishment and the past) and FT Marinetti (representing the Futurists). Nevertheless, in its short-lived existence, this movement gives birth to a whole new aesthetic, and a whole new modernism. Wyndham Lewis, Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, Jacob Epstein, David Bomberg, Ezra Pound; they are modern people of the machine age.

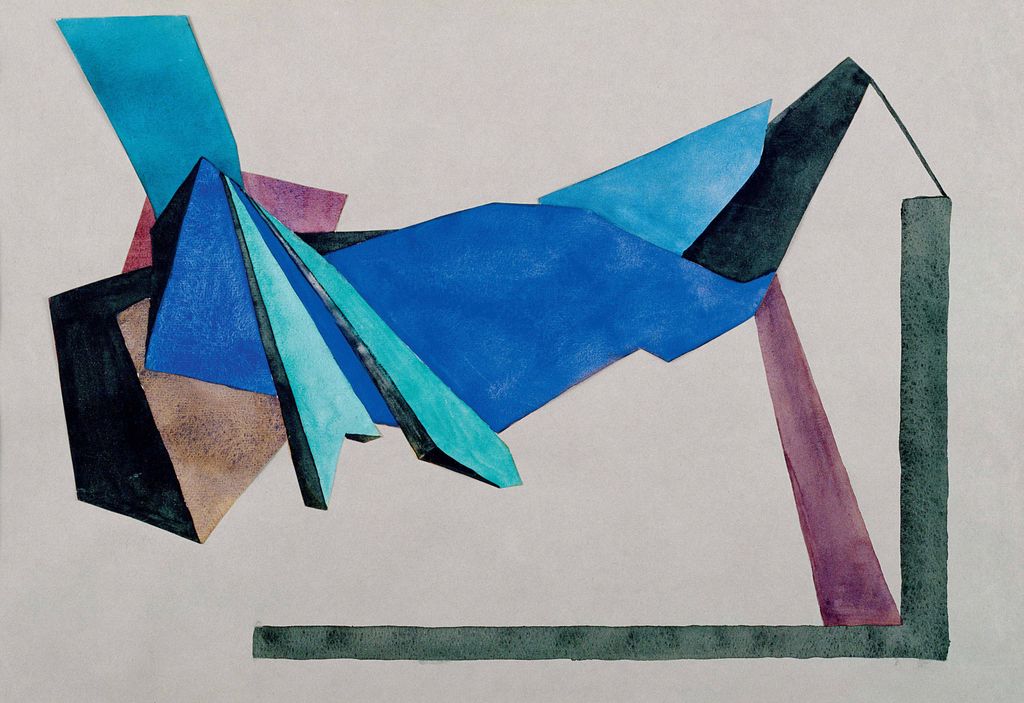

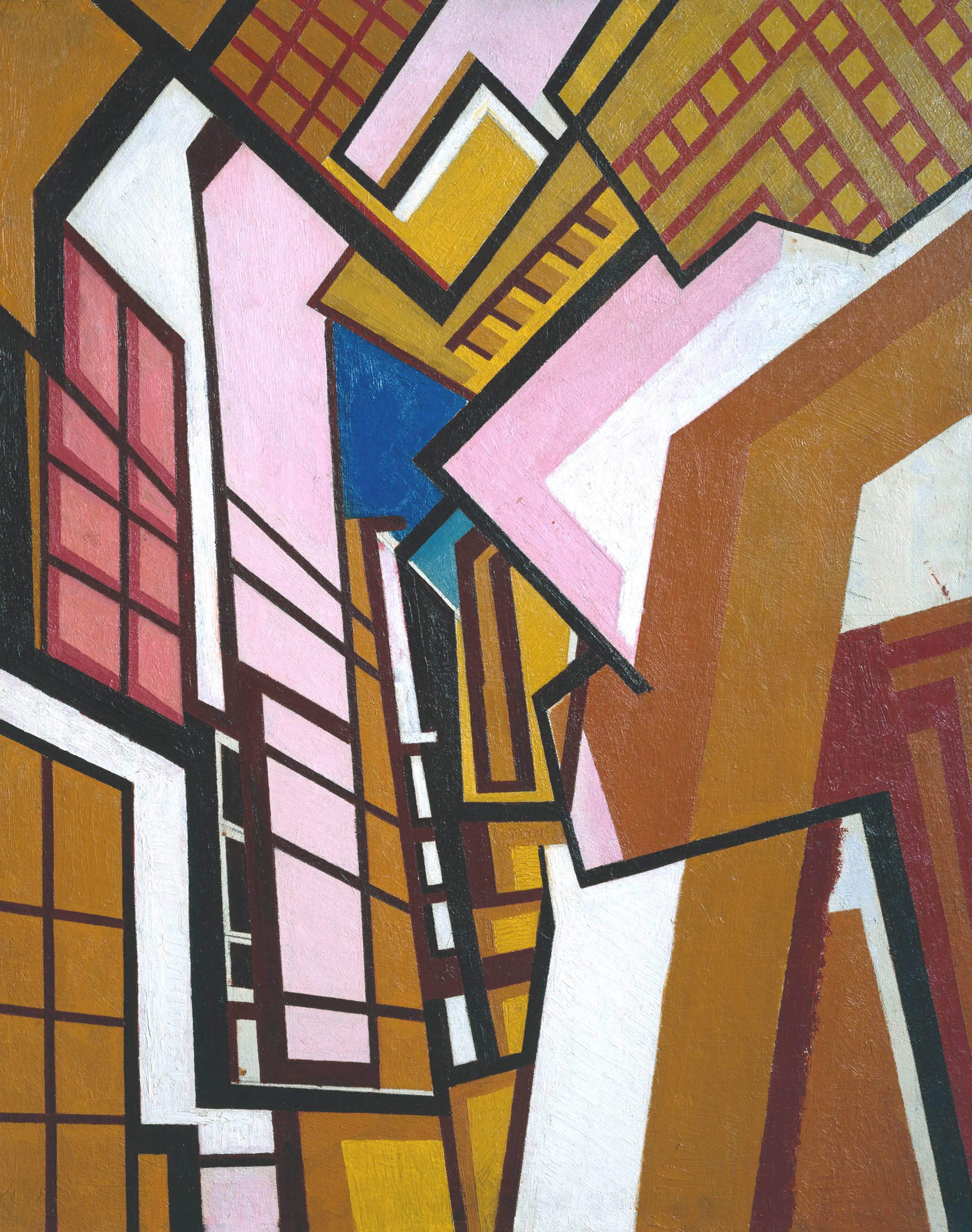

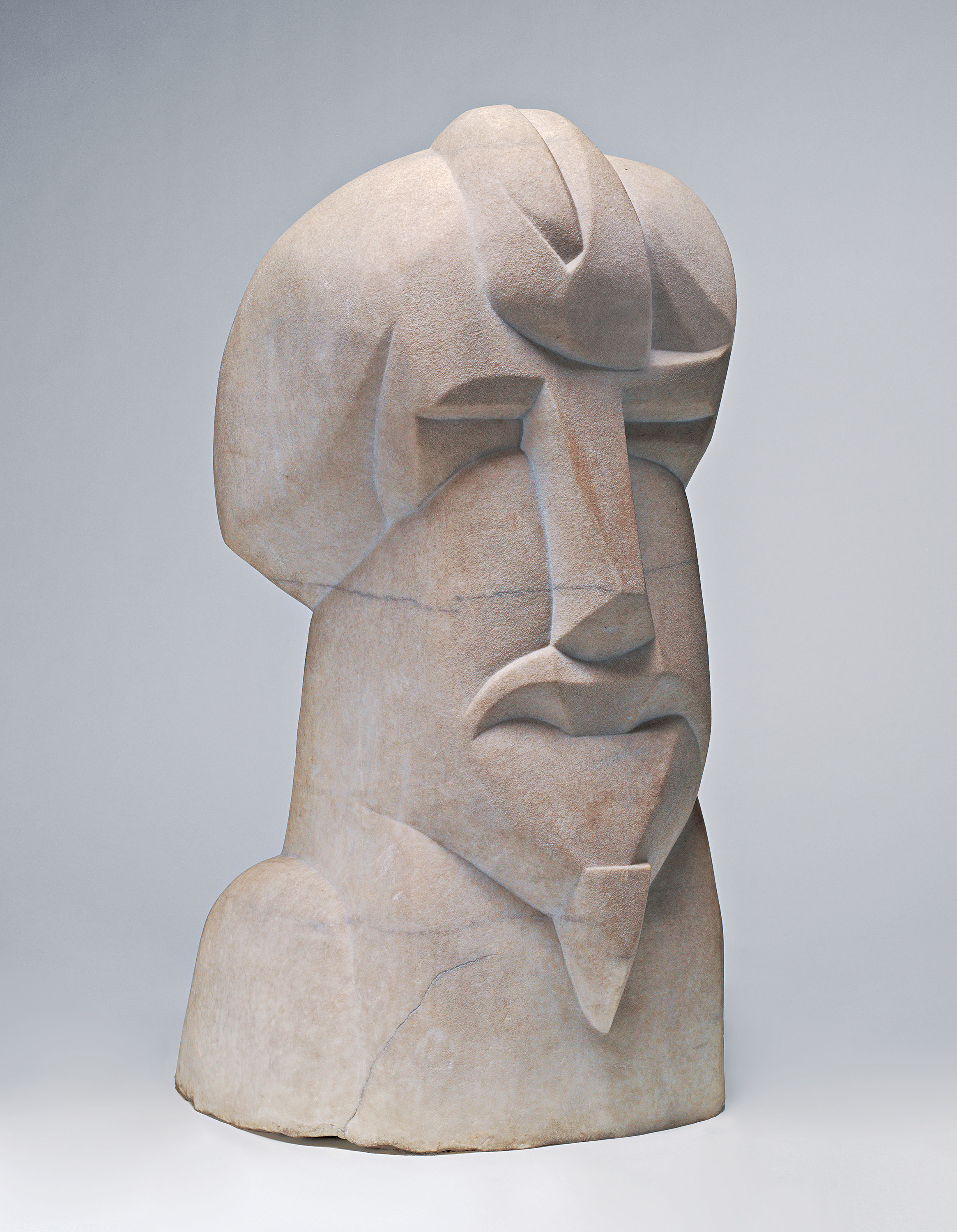

The sculptor Henri Gaudier-Brzeska becomes an important figure in the group as he creates pieces that echo the machine age while simultaneously draw inspiration directly from the totemic figures of primitive art. Sharp lines and angular abstract shapes become the language of painter David Bomberg. NWR Nevinson falls within the aesthetic of the group too (although he ends up being publicly condemned by the group, remaining, as it were, a loyal follower of Marinetti...). The dynamic work produced during the few years of the group’s existence celebrates the Present and the ‘crude energy of the world’. This is in 1914. The First World War is just around the corner.

BLAST was to have only one more issue: BLAST (No. 2) – War Number. This was published in 1915, featuring for the first time in print the poet T.S. Eliot. The First World War already under way, it is clearly reflected on the pages of BLAST. Although previously bright pink, this issue’s cover is strictly black and white throughout. The artists’ struggle to assert the relevance of art and culture within the context of one of the bloodiest wars in world history is evident. Henri Gaudier Brzeska writes from the French trenches. His letter, as published in the review, concludes with the announcement of his death. He was 23. His creative life was tragically short. Jacob Epstein starts re-working a version of the ‘Rock Drill’. This time, the sculpture is no longer an apotheosis of the machine age. It is cut in half – only bust size – and its right arm is amputated. The message is clear.

Only 1 year after their official appearance on the scene Vorticism has already become irrelevant. The work of Wyndham Lewis becomes increasingly political. Nevinson, who is now an ambulance driver at the war front, becomes a war artist bringing Vorticism to the trenches, making it the language of WWI. The Vortex is everywhere in the visual language of war-ridden Europe. It is sound and pain and harsh, cold metal; it is blinding lights and new, dreadful experiences.

The Vorticists only ever had two shows. One in London in 1916 at the Doré Galleries, and one in New York City, at the Penguin Club in 1917, organised by Ezra Pound and sponsored by the collector John Quinn. Nevertheless, this short-lived movement that came out of London contributed massively to the Art Deco aesthetic that was to following in the 20s and 30s. This is most evident in the Vortographs of Alvin Coburn, also on display at the Tate.

Even if there’s only a few more weeks to go before the exhibition closes, and even if you are heading out to places exotic and warm instead of rainy London for your holiday, it would be very much worth your while to see this exhibition. Failing that, Google the artists. They are very much worth your time.